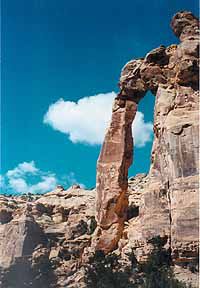

| BLM land on the Swell at Eagle Arch. |

In a recent Emery County Public Lands meeting, Dennis Worwood, public lands chairman picked out excerpts from the Federal Land Policy Management Act and highlighted them as well as offered a clarification for these regulations. Part II of this series explores the issue of public land management further:

Definition: The term “withdrawal” means withholding an area of federal land from settlement, sale, location, or entry, under some or all of the general land laws, for the purpose of limiting activities under those laws in order to maintain other public values in the area or reserving the area for a particular public purpose or program.

Worwood’s comment: Lands that receive some designation typically go through two processes: first, they are withdrawn, meaning that the government will never sell or dispose of them, and some uses of the land are generally also withdrawn, such as “the land is withdrawn from mineral entry,” which means that mining will not be allowed. The second step is reservation, in which the land is “reserved” for some special purpose, such as wilderness.

Consistency clause: …to the extent consistent with the laws governing the administration of the public lands, coordinate the land use inventory, planning, and management activities of or for such lands with the land use planning and management programs of other federal departments and agencies and of the states and local governments within which the lands are located. In implementing this directive, the secretary shall, to the extent he finds practical, keep apprised of state, local, and tribal land use plans; assure that consideration is given to those state, local, and tribal plans that are germane in the development of land use plans for public lands; …assist in resolving, to the extent practical, inconsistencies between federal and non-federal government plans, …provide for meaningful public involvement of state and local government officials, both elected and appointed, in the development of land use programs, land use regulations, and land use decisions for public lands.

Such officials in each state are authorized to furnish advice to the secretary with respect to the development and revision of land use plans, land use guidelines, land use rules, and land use regulations for the public lands within such state and with respect to such other land use matters as may be referred to them by him. Land use plans of the secretary under this section shall be consistent with state and local plans to the maximum extent he finds consistent with federal law and the purposes of this act.

Worwood’s comments: This is the often-cited consistency clause, which tells the BLM to involve the state and counties in planning and decision-making processes. It is sometimes misquoted or misconstrued to mean that the BLM must make its plans conform with county master plans. FLPMA directs the BLM to consider the county’s plans, but only to “…the extent practical”, or to the “…maximum extent consistent with federal law.” The bottom line is, BLM plans must comply with federal law. If county plans are consistent with federal law, then BLM plans can (or will) also comply with them. For example, the county may wish to have some gravel pits on BLM land to make it possible to maintain roads in the Swell. If the county located a gravel deposit that was home to an endangered species, the BLM must comply with the Endangered Species Act rather than the county plan.

Where no resource conflicts exist, the county has some extra leverage to use on the BLM, thanks to the consistency clause. But the clause is certainly not as powerful as some folks make it out to be.

Multiple use and sustained yield requirements applicable; exception: The secretary shall manage the public lands under principles of multiple use and sustained yield, …except that where a tract of such public land has been dedicated to specific uses according to any other provisions of law it shall be managed in accordance with such law

Worwood’s comments: Again, FLPMA would be a multiple use law if the statement stopped after the word “yield.” However, it continues to say that when a piece of land has received some type of designation (wilderness, national conservation area, monument, etc), it will be managed according to the act or proclamation that created it. Notice that the words “…to the extent practical” are not used here as they are in the consistency clause. When land has been designated, it will be managed according to the act or proclamation, period. If the act does not specify how a certain activity is to be managed, then the rules of FLPMA apply. For example, grazing may be managed under the rules of FLPMA inside wilderness or national conservation areas, unless the act creating the areas says otherwise. FLPMA creates two broad classes of BLM land: Lands that will be managed under FLPMA for multiple use, and lands that receive some designation and will be managed under the act that created them. In each instance, the county’s goal is to have management that is consistent with local needs and desires. In the case of multiple use lands, we can best do this by participating in the development of resource management plans. On lands that will receive some type of designation, we must work to see that the act or proclamation is consistent with local desires, since the land will be managed according to that document. Of course, the BLM must also develop management plans for designated areas, but we cannot rely on the planning process to protect us if the act or proclamation is contrary to our wishes. For example, if a wilderness bill created boundaries or water language that were contrary to county wishes, we couldn’t “fix” things through the resource management plan. This is why Emery County got into the business of proposing NCAs and even a monument. decision makers in Congress and the Dept. of Interior have consistently and repeatedly told us that the Swell WILL receive some type of designation. (Even our own congressmen and senators have told us this.) Our task was to find a way to influence the law that will ultimately guide management on the Swell. We took a direct approach and attempted to draft the law ourselves. We were not successful in those attempts. I still believe that we did the right thing by trying to protect the county’s interests in this manner. When Congress finally tackles the Utah wilderness issue in earnest, we will have to find a way to incorporate county wishes into the Bill. I’m not sure how to do that.

Roads “grandfathered”: nothing in this subchapter shall have the effect of terminating any right-of-way or right-of-use heretofore issued, granted, or permitted.

Worwood’s comments: Revised Statute 2477 of the 1872 mining law granted everyone the right to create highways, at will, across public land. That right was revoked by FLPMA, but the above statement makes it clear that existing right of ways would be recognized. In my opinion, Congress made at least three major mistakes in FLPMA’s handling of roads: First, FLPMA did not direct the BLM to conduct an inventory of roads to determine how many existed in 1976. We are now in the process of trying to document which roads existed 30 years ago. Second, FLPMA did not define what a “highway” was. We are still arguing about what a road is. Finally, FLPMA did not define “construction”. Can roads be constructed through use, or must there be deliberate planning and construction? Since Congress didn’t define the term, we are stuck with whatever definition the current secretary of interior or the latest court case give us.

Wilderness review deadline: Within 15 years after Oct. 21, 1976, the secretary shall review those roadless areas of 5,000 acres or more and roadless islands of the public lands, identified during the inventory required by section 1711(a) of this title as having wilderness characteristics described in the Wilderness Act of Sept. 3, 1964.

Worwood’s comments: The 1964 Wilderness Act did not apply to BLM land. Only land managed by the forest service and national park service was eligible to be designated wilderness. FLPMA expanded the Wilderness Preservation System to include BLM land. This is further proof that Congress did not view FLPMA as the solution to all management problems on BLM land. If FLPMA was capable of providing protection to all BLM land, why did Congress make BLM land eligible for wilderness, order the BLM to conduct a wilderness inventory, and give them a deadline to do so? I wish FLPMA had ordered the BLM to inventory roads and settle RS-2477road claims before doing a wilderness inventory. It might have made the issue clearer and saved us a lot of trouble.

Non-impairment clause: …the secretary shall continue to manage such lands according to his authority under this act and other applicable law in a manner so as not to impair the suitability of such areas for preservation as wilderness

Worwood’s comments: This states that wilderness study areas must be managed in a way that does not impair their ability to be designated as wilderness. The non-impairment clause is the basis of SUWA’s lawsuit challenging the use of ATVs on the Devil’s Racetrack and the Eva Conover Road. SUWA claims that ATVs cause erosion and noise that impair the wilderness qualities of the area. Judge Kimball heard SUWA’s case, and while acknowledging that ATVs had caused some damage, he felt that the BLM was taking adequate steps to address the problem. SUWA appealed the decision to the 10th District Court in Denver, arguing that taking steps was not enough-the BLM absolutely MUST preserve the wilderness character of the area. The district court bought SUWA’s argument and ordered Judge Kimball to take another look at the case. His decision is still pending. The 10th District ruling is a big deal because it might greatly expand the court’s ability to dictate management on public land. In the past, courts simply looked at process�did the BLM go through the right steps in making their decisions� but did not try to second-guess the BLM’s decisions.

If SUWA prevails, the court will rule on whether the BLM is actually doing the right thing. If that happens, the courts will be cluttered by suits from all kinds of special interest groups who want a judge to over-ride the BLM.

That would be a nightmare.

Debates will continue on the use of public lands in Emery County.

The Emery County Public Lands Council meets the second Tuesday of each month at 10 a.m. at the county building.