By By

Editor’s Note: This is the second in a three-part series on some of the events which shaped the history of Emery County.

By PATSY STODDARD

Staff, Emery County Progress

The irrigation canals have long been an integral part of the Emery County landscape. To look at an irrigation canal you might not think of how much work it took to build that canal in the time before backhoes and other motorized equipment.

When all you had to work with was a shovel it amounted to a tremendous amount of digging. When settlers began moving into Emery County in the late 1870s all of the settlements that sprang up were near creeks where the settlers could access water supplies. In Edward Geary’s book, A History of Emery County, he said, “Despite the fact that Muddy Creek was the first sizeable stream encountered by travelers who reached Castle Valley by way of Wasatch Pass, potential settlers seem to have passed over the region during the 1870s because both the creek and the available river bottom farm land were somewhat smaller than those farther north.”

Casper Christensen had been in the area for several years grazing livestock. He was the first settler to take the construction of an irrigation ditch from the planning stages to actual implementation. He began the construction on May 15, 1881. According to Geary, Christensen’s land was on the right bank of Muddy Creek about three miles northeast of the present townsite of Emery. Also in 1881 Joseph and Marinus Lund and Charles Johnson selected land upstream from Christensen, but Johnson and Joseph Lund soon became discouraged and returned to Spring City. Christensen then moved his family into the cabin built by Joseph Lund. At the end of the season he had harvested 70 bushels of wheat. That same year, Miles and Daniel Miller located several miles downstream in what came to be know as Miller Canyon.

Geary said, “As the settlement on Muddy Creek grew other familes were locating in the valley of Quitchupah Creek, six miles to the southwest. Shortly after the turn of the century, a cloudburst on the creek’s headwaters sent a massive flood through the valley, destroying the diversion dams and canals and turning the creek bed into a deep wash. Even though an extension of the Emery Canal restored irrigation water to part of the land, most settlers either moved into Emery or left the region.

“Even before the disastrous washout, Quitchupah Creek was too small to irrigate more than a few farms and the Muddy Creek Valley had limited land suitable for cultivation. It was natural, therefore, that the settlers’ attention should be drawn to the bench dividing the two valleys. Here was sufficient land for a sizeable community. In order to bring water to the site, it would be necessary to construct a highline canal for four miles along the base of the mountains. Preliminary work on the canal began in 1885, and in 1886 a stock company was incorporated with Heber C. Pettey as president, Casper Christensen, vice-president, Peter V. Bunderson, secretary and treasurer, and William G. Petty, George Collier, and George Whitlock as directors. There were 58 men who subscribed for stock in the new company. The greatest barrier in the path of the canal was a large shale hill.

“To go around the hill would lengthen the canal by more than two miles and bring it onto the bench at a lower level, thus reducing the amount of land available for irrigation. After some discussion, the company decided to dig a tunnel through the hill, a project that also required building a dam across a ravine in order to deliver water to the tunnel. The tunnel would be 1200 feet long and all of it through solid rock. This did not deter the men for they were men of courage, ambition and hope.

“The building of the Emery tunnel required both ingenuity and tenacity. Existing in a subsistence economy, with no capital to speak of and no trained engineers, nothing but the most rudimentary tools, the settlers labored for two years to complete the tunnel, doing most of the work during the winters. They calculated the proper fall with a homemade water level and sighted over lighted candles to keep the tunnel correctly aligned. To expedite the work, they sank, a shaft in the center of the hill so they could work from four ends at the same time. When the various segments met, they were almost perfectly aligned,” said Geary.

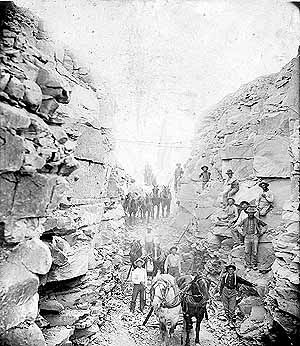

According to the Emery County Historical Society book on the history of Emery County from 1880-1980, “The dirt was carried out of the tunnel by buckets and horses or mule power. The tools of the men were only picks and shovels, blasting powder and two wheeled carts to carry out the dirt. The continuous caving of the roof and sides made the work very hazardous. Many stories are told of miraculous escapes by men who were inspired to move just before a cave-in. These were a religious people who believed in and received help from the Lord.”

In the Castle Valley Daughters of the Utah Pioneers book there is a passage which reads: “On one occasion Isaac Allred and Rasmus Albrechtsen were hired to remove a great pile of rock that had fallen down. After working most of the day until they were tired and hungry they left the tunnel to eat lunch and rest a few minutes. When they returned, a slab of rock weighing approximately two tons had fallen where they had been working.”

“Water was turned into the tunnel in 1888, but a new set of problems developed almost immediately. The Blue Gate shale through which the tunnel had been dug is hard and tightly compacted in its original state, but once exposed to air and water it softens and sloughs away. Recurring rockfalls blocked the tunnel. In an effort to solve this problem, the entire length of the tunnel was timbered on the sides and top, a project requiring several months to complete. But rocks continued to fall from the roof, breaking the timbers. The timbered sides made clearing the channel more difficult as there was no room to push the rocks to the side and it was therefore necessary to carry them all the way to the end of the tunnel. One large rockfall in the midsection caused the upper half of the tunnel to fill with muddy sediment three feet deep, which required six weeks to remove. After much discussion, the company stockholders decided to take out the timber, as it seemed to be doing more harm than good. They then converted the lower half of the tunnel to an open cut, an undertaking that required almost an additional year,” said Geary.

Kathleen Truman of the Emery County Historical Preservation Commission said, “The settlers held a community party to celebrate the completion of the project. For the celebration they had a feast of roasted rabbit, which goes to show the conditions of the people at the time that all they had to celebrate with was the rabbit dinner. During this celebration a loud roar signalled that the dam had collapsed across the ravine leaving the tunnel high and dry. True to the form of these settlers they did not give up and proceeded to construct a new canal segment above the ravine.”

In his book Geary said, “The shortened tunnel was easier to keep clear. Over a few years time, the shale which kept collapsing formed a natural arch eight to 10 feet high and rockfalls became less frequent. In this form the tunnel continued to serve for some 75 years before being replaced by an open cut excavated by heavy equipment.”

The Daughters of the Utah Pioneers constructed a monument to keep the story of the canal alive. This monument gives a brief history of the tunnel and commemorates this valiant achievement.

Truman said, “Eighty percent of the Muddy Creek goes to Emery while 20 percent is diverted to Moore. You could always tell where the ditches ran because they were lined with cottonwood trees. When modern heavy equipment became available the earth was simply dug away to make an open cut alongside the tunnel in the blue slate mancos shale ridge. The open cut was successfully made in the spring of 1956. The water would then run through an open canal. The blood, sweat and tears of many years of hard work was erased by the digging of a backhoe into the blue shale. These memories and pieces of history are important to be preserved. Any pictures detailing the canal building and its subsequent modernization should be preserved for future generations. Those involved in shaping the future need to be aware of the hard work and endeavors of those who have come before.”

According to present day Mayor of Emery, Mike Williams, Emery Town still relies on the use of canals to get their drinking water. The water originally came down into a settling pond next to the cemetery and then it was used by the people. A water treatment system has since been installed.

Mayor Williams is seeking funding to modernize the water system into the town of Emery. A pipeline will be installed along the ditches to bring the water into the town. The use of a pipeline has many advantages to the old canal system. The issue of salinity control is always a concern in this country of alkali. The pipeline reduces the salinity in the water. Large amounts of water are saved with pipelines because the water doesn’t seep out along the ditch banks. Mayor Williams well knows the advantages of the pipeline, his major obstacle is the securing of funds for this project. As Emery moves into the future the issue of a safe and secure water source continues to be a concern.

Editor’s Note: Next week in the final part in the Looking Back series, the history of saw mills in Emery County will be explored.