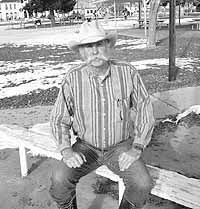

Crockett Dumas, district ranger for the Ferron Office of the Manti-LaSal National Forest is retiring after 32 years of service. Dumas was born in Avery’s Creek, N.C. and attended school there.

Dumas said, “I attended college at the University of Montana. I found the state that had the lowest population per square mile and a forestry school. From the time I was 9 years old I wanted to be a forest ranger. I loved to fish, trap and hunt. I’ve done a lot of things I have cut hair and run liquor. In North Carolina there are a lot of summer camps for the high dollar kids and I was a camp counselor.

“During two summers I worked at Glacier National Park as a park ranger. We educated people on how to avoid adversarial contact with grizzly bears. I started with the forest service in 1969 in the Bridger National Forest, the Wind River Range in Wyoming. I was a wilderness ranger and helped people and gave out information. I spent a lot of time in the field helping people. One time I was up about 13,000 feet and there was a couple out backpacking. The lady lost her shoes in the stream while crossing it. I gave her a pair of red tennis shoes and she made the rest of the trip in those. We worked with clearing trails and livestock and sheep permitting as well.

“I was in Wyoming until I won the lottery in 1969. I was in Vietnam for 18 months. I started off as a medic. I was trained at Fort Houston. I was a forestry and range adviser in the Quang Tri province. We ran a nursery and grew papayas. We also did hog projects. We took hog manure and put it into culverts and capped one end. Then we would cut a hole and use the gas produced to heat tea and cook with. We taught the natives how to do this. The Montagnards are like the Native Americans, they wore dresses, made jewelry and smoked pipes. They carried things on their backs in packbaskets. Every day they would make the trip down the mountain with twigs in their baskets to sell to the Vietnamese for fuel. Down and back was a 15 mile trip.

“We also made charcoal kilns and taught them how to produce charcoal. Americans would send flower seeds to us and we would plant the seeds. I learned a lot over there. Vietnam didn’t change me……. I was still a shiftless woods loafer.

“When I returned home, I taught school for seven months. I taught earth and life science to 7th and 8th graders. This was the hardest job I ever had. I’ve always respected teachers, but this experience increased that respect.

“I met my wife Sharon Dumas at the horse races. We participate in endurance riding.

“I went back to work for the forest service in Idaho City in the Boise National Forest. I worked with the first group of certified civiculturists. They are gurus of trees. Even though I said I would ‘never go to Utah’ I went to Utah State for some training. I learned a lot but I didn’t appreciate the experience. I went to Escalante in 1975 in the Dixie National Forest. I worked with timber, fire, recreation and minerals. I also have a degree in forestry wildlife management. We could do more for wildlife than if I had been working for the Division of Wildlife Resources.

“I have always cracked heads with the bureaucracy. I think there is too much paperwork and not enough time spent out on the ground. It’s so easy to get office bound. I think developing relationships is the most important part of my job. The forest belongs to the people and it is our job to manage it.

“I was in Escalante until 1983 at which time I moved to Northern Idaho to the St. Joe’s National Forest. This is in Idaho’s panhandle. I was the district ranger there and for four months in the winter we were without sunlight. The Bitteroots are beautiful, rugged and rough. I was the ranger, the sheriff and the bishop, whatever happened we handled it. It is really unforgiving country. We did a lot of rescues getting people out of the river and people sliding off the road. It was almost a rain forest there. The red cedar trees grow to 20 feet in diameter. I spent six years there. We had the first prescribed burn for that area. There were big elk herds in the area. In 1910 there was a big fire in the area and a man named Polasky saved a lot of people by putting them in a tunnel and keeping them there. He held them at gunpoint. More than 300 people were killed in that fire. There was a lot of history in the area which I enjoyed. The Burlington Northern railroad went through there. There was a lot of snow, rain and moose.

“I went to New Mexico in 1990. I managed two districts. The Taos Penasco and the Camino Re’al which means the Kings Road. Which was what they called the road from Mexico City to Taos.

“The King of Spain gave land grants in this area but in the war with Mexico this all changed. This was a very contentious area. New Mexico is where I got my PHD in life. In this area there were two officers who were shot at, a ranger station was bombed and a barn burned.

“There was a real blow up when I went there in 1990. A meeting was held and people kept coming until finally the meeting was held in the parking lot. Where things are the worst there is the most opportunity. There were a lot of circumstances and we changed the forest service from authoritative to management and became facilitating and a resource.

“The amount of services on the unit had been going constantly down and the cost per unit had been going up. The environmental movement started in 1965. We spent from 1965 to about 1978 learning about impacts. The interest in public lands grew. Rangers made plans for their quads. In 1970 the National Environmental Protection Agency came up with a management plan that is renewed every 10 years. Rangers worked on these plans without any public involvement. In 1987 the first approved forest plan was not successful because it created adversarial relationships. Those involved in the planning process were not out on the ground. In New Mexico we reversed this and developed relationships.

“We worked together with the land grant people in the Pecos Wilderness area. Timber down there is really important. Most of the homes are heated with wood. The environmentalists and the grazers worked together. Costs went down and production went up. These people lived on the forest every day. Ski touring, picnicking and riding horses. They had a real affection for the forest. We made people happy and formed good relationships and it was fun. I learned so much. I learned that management is not a game of checkers but of chess with many players moving in all directions.

“We received Harvard’s top award for innovation in government for our work in New Mexico. Everyone became involved, environmental groups, nonprofit organizations. We improved watershed, wildlife and fire dangers. We used prescribed burns and the land banks to improve grazing. The University of Colorado and North Carolina State is collaborating on a book about what we did in New Mexico called the “Camino Re’al Policy: The Challenge of Sustaining the Common Interest. They contacted me to read the draft copy and work with them on it. This book is about the work we did in New Mexico bringing the interests together.

“In January of 1999 my wife announced that she was going to Utah and she put the house up for sale. It sold in three days. So I lateraled over to the Ferron office. Moore is the most populated place I’ve lived in since Missoula. I always wanted to come to Ferron. These are the best people I have every lived around. If someone breaks down people around here stop to help. People here will give of what they’ve got. People here are different. I have been fortunate to live in these places and make a living and enjoy the natural resources.

“I am not retiring, just graduating to the horse ranch in Escalante. I’m not a watcher, I like to do things. We go on a horse ride along the outlaw trail which is a 275 mile

District Ranger Graduates to the Ranch