Interstate 70 which divides the San Rafael Swell is a unique road through some of the most scenic terrain in the United States. People traveling cross country often marvel at the diverse vistas along the way. Most pass through the area without a thought to the history behind the road. Prior to I-70 a road didn’t exist between Fremont Junction and Green River. Travelers wishing to travel to Green River and points beyond would travel through Salina Canyon and up SR-10 through the small towns of Emery County to Price and back down SR-6 to Green River.

With the construction of I-70 a shortcut was devised which cut off many miles of travel for motorists. Previous to the construction of I-70, much preparation work was involved.

The idea for interstate highways was implemented by Pres. Dwight Eisenhower who saw the advantages of an interstate system across the United States. The original intent was for the moving of the military at great speeds with minimal stops.

The money for the interstates came from the National Defense Highway fund. Most of the roads which became interstates coincided with existing roads or were constructed over the top of existing roads. This was not the case with I-70. In the beginning three different routes were considered for I-70. One route was to go from Fremont Junction to Price to Woodside to Green River. Another alternative was to go from Fremont Junction to Castle Dale, across Buckhorn Flat and come out just south of Woodside and on to Green River. The other alternative was from Fremont Junction across the Swell to Green River.

Bill Arns, location engineer for UDOT was involved in preparing preliminary maps of the San Rafael area where the interstate would be located.

Albert Spensko, Clyde Olsen, Bill Austin and Rex Oviatt were all involved in the early construction of an access road which would determine the alignment of the I-70 interstate. Austin, Oviatt and Olsen were all from Emery County and Spensko from Carbon County.

The decision came to place the road across the San Rafael Swell because this land was largely public domain, uninhabited and no purchase of rights-of-way would be needed to complete the work. This was also the shortest route which would save on construction costs.

Spensko, Arns and region 4 district director Quint Adair were on the initial flight to scope out the Swell.

Spensko said, Bill Wells, UDOT station foreman in Hanksville was hired with his plane to fly the route. “Wells was an experienced pilot, he had been flying in and out of the canyon country for many years and was involved in rescues. He was very familiar with the area between Hanksville and Green River.

“Approaching the east end of the San Rafael Reef is one of the most awesome, striking sights I had ever seen. It was indescribable. As we flew the area it became apparent that a great deal of the Mancos Shale would have to be traversed in construction of the road. Heaving and swelling of the shale is very pronounced and produces difficulty in constructing roads over the shale. Bill took us right into the canyon at Spotted Wolf and I had a close up look at the sides of the canyon from both sides, I think I left finger impressions on the arms of my seat. Several geological figures stood out as we flew the area. One of the most notable was Spotted Wolf. The steep Wingate vertical walls would present a challenge in the future.

“Another notable feature was Ghost Rocks, Eagle Canyon and Devil’s Canyon. From the air it looked like an impossible area to cross. You can’t fully

appreciate the depths of those canyons from the air. Fortunately the proposed alignment would not have to cross Devils Canyon at any point, the alignment would only parallel the canyon rim through the desolate gypsum beds to the confluence of two dry creeks, Bitter Seep and Salt Wash. There is a mound of marron siltstone found at the junction of Bitter Seep and Salt Wash. This isolated piece of the Summerville Formation stands as a monument and would be a visible landmark seen for many miles to assist our route location and would play an important role in the ground work that was to come. Other geographic formations is the Entrada formation, it would serve as a land mark as well. There are gargoyle figures which make up Goblin Valley although there aren’t as many in this area as there are in Goblin Valley. Traveling west from there we entered the multicolored Morrison Formation which is the home to uranium and dinosaur remains. This formation would present numerous construction problems in the future. In the flight we only encountered one yearlong stream and that was the Muddy River. Flying this uncharted area was one of the highlights of my UDOT career.

“The Swell had a lot of roads all over, but there wasn’t a road directly from Fremont Junction to Green River. This was all virgin territory. The district director Quinn Adair and I along with the pilot, Bill Wells flew the area several times. I was able to distinguish all the landmarks in the area as they corresponded on the map when we started the ground work.

“This project preparation work began in January of 1959 and in November, Bill Austin, Clyde Olsen, Rex Oviatt and I took a 4-wheel drive truck, a bobtail truck, a dozer and a campwagon to start the work. We started on the east side of Black Dragon. The whole area where I-70 goes now was inaccessible in those days. Our job was to provide an access road as close as possible to the alignment as established on the strip map. We started at Black Dragon, first crossing the San Rafael River, which proved to be more difficult than we expected. We were to start at Black Dragon and meet Rex at Jerry’s Flat.

“But, it took so long to get across the river and rebuild the road all through the Black Dragon, so we didn’t meet him until the next day. It was almost dark when we got through the Black Dragon canyon and we knew we weren’t going to meet Rex. So I told Bill Austin, who was the dozer operator that I remembered a cabin near an old uranium mine. When we flew over the area I remembered seeing the cabin there on the west side of Black Dragon canyon. So we took the pickup and found the cabin. We spent the night in the cabin. We were pretty hungry and our lunches were long gone, since we were supposed to meet the camp wagon that night, we didn’t have any extra food with us. We found some pancake mix in the cabin and syrup and coffee, because the cabin owners had just been there some time before, working their claim. So we ate pancakes that night, had a nice cup of coffee and then the next morning we left them $2 and a note thanking them for the use of their cabin and the food. We proceeded to build the road and finally we met Oviatt at Jerry’s Flat.

“This was late November, it was cold, but the weather wasn’t too bad. The strip map had been prepared from the aerial photos and we followed it as closely as we could. We tried to stay on the center line and within the corridor as closely as possible. There were some places, like Eagle Canyon and Devil’s Canyon where this wasn’t possible.

“From Jerry’s Flat we headed up Sagebrush Bench, up Crawford Draw to the head of Sinbad. When we got to Ghost Rocks we followed the old road to the bottom of Eagle Canyon and from there to Justensen Flats. We spent three days rebuilding the road from Eagle Canyon to Justensen Flats. There had been an old road through there, but it hadn’t been used in a long time and needed a lot of work to make it passable. When we got to Jerry’s Flat there was a sheepherder there. He had seen our dust from the equipment and saw us coming across the flat. He came out to meet us. He asked ‘what in the hell are you doing out here.’ We told him we were working on a road and there was going to be an interstate highway through here. He laughed at us told us we were crazy and we shouldn’t be wasting money on such a project.

“We stayed that night at the sheepherder camp and enjoyed a few spirits with the herder. The next day we proceeded up Sagebrush Bench, up Crawford Draw to the head of Sinbad. We just pulled our campwagon along and Rex was the chief cook and bottle washer. We had a lot of sour dough biscuits, I might add.

“We worked Monday-Thursday for 10-12 hours a day for as long as there was daylight. On Fridays we would come back into town to resupply and get ready for the next week. At the end of each day we just camped where we finished the road that day. I would mark the line ahead for the next days work. We built 80 miles of access road from November 1959 to May of 1960. There were several ranch roads through the Swell. There was a ranch road out to Copper Globe, but across the top of Devil’s Canyon there weren’t any access roads. We stayed as close as possible to the alignment outlined on the strip map, but we ran into problems at the top of Devil’s Canyon. We couldn’t find a way down to Salt Wash.and Bitter Seep. The gullies in the gypsum deposits were so large and long the dozer wasn’t big enough to get the job done in the alloted time.

“One morning we got up and it had snowed about an inch during the night while we were camped near Devils Canyon. We saw wild horse tracks in the snow around the campwagon. So we decided to follow the tracks thinking that the horses had to go for water. So we followed the horse tracks and they provided a path down into the Salt Wash-Bitter Seep area. That is one of the few places we deviated from the actual alignment. From there we followed the line up to the Muddy River. We deviated around some formations to get on top of the Bench at the Muddy. From the Muddy we headed to Dog Valley. We couldn’t get up the ledge at the top of Dog Valley so we backed up and intercepted the road to the Baker ranch. It took several days to get across there. We got back on the alignment from the Baker Ranch road to Dog Valley and from there to Fremont Junction. We built the access road as close to the center line as possible, there was a corridor we needed to stay within. At that time SR-10 went through Salina Canyon and it was a two lane highway.

“Our crew didn’t go past Fremont Junction,” said Spensko.

Strange things seemed to happen on this project. One night the crew was in the campwagon parked in the middle of the newly constructed road near Ghost Rocks, when a knock came at the door. The workers were surprised because no one was usually out on the Swell late at night. It turned out to be two workers from the Atomic Commission and they were lost and looking for a way out. They were given instructions on how to get out and told they would come out by the town of Cleveland.

Spotted Wolf would present some unique problems to the construction of I-70. It was determined that was the best possible route for the road in that area, but the canyon was narrow, only 16 inches wide in spots. Sheep had been known to become stuck in the narrow canyon. The original intent was to go northeasterly from Spotted Wolf through Buckmaster Draw and intercept the county road. But at that time many uranium mines in the area were very active. It was determined the road would not go through the uranium mines. It would go directly from Spotted Wolf across the mancos shale to Green River.

Spotted Wolf was one of the biggest rock jobs undertaken on the route. In September of 1967, UDOT opened up bids for an eight and a half mile section of I-70 to be placed in Spotted Wolf Canyon. For about $4.5 million, Morrison and Knudsen Company of Idaho agreed to blast and chisel the canyon to accept a 141 foot road bed and a 15 foot channel change for the natural drainage. Approximately 3.5 million yards of excavation was involved in removal of the sandstone ledges.

Another formidable task in the construction of I-70 was the bridge across Eagle Canyon. The first bridge was constructed by crews operating from both sides of the canyon. High line towers were used to lower the two halves of the arch span into place. The spans were supported by giant hinges and were jointed in the middle with splice plates held together with wrist size bolts.

Spensko said, “I want people to know how this access road was built which was the precursor for our modern I-70 we enjoy today. These other three men and I started this work 50 years ago. I know the people of Emery County will be familiar with all the sites in the Swell. Not many people know today of the preliminary work which was done before the actual road construction could begin. I have been involved in many road projects in southeastern Utah. Throughout the construction of I-70. I was involved as a material engineer and doing the geo-technical work and the quality control from conception to the construction on the projects. The first construction project on I-70 was from Dog Valley towards Salt Wash. We didn’t want the road visible to the public because they might think there was a usable road through there. The first project was seven miles and HE Lowdermilk was the contractor and the first company to work on I-70. There were different projects laid out in different areas. We didn’t just start on one end and work our way through.

“Some of the first projects also built were from Green River to US 06 Junction and toward Spotted Wolf Canyon. There were projects throughout the Swell and companies like LeGrande Johnson, Morris and Knudson, Strong Brothers, WW Clyde, LA Young and others worked on the projects. It was an economic boom for our area for 20 years.

“During the initial construction, four lanes were built in some of the more critical areas, but only two of those were paved intially. Construction went on through the late 70s. It was a huge project through a totally inaccessible area. The thing about I-70 is it’s built through a geological masterpiece. The unusual geological characteristics across the Swell, just don’t exist anywhere else. The San Rafael Reef is a jagged outcropping of rock that extends approximately 60 miles in length and juts hundreds of feet into the sky. The change in elevation out there is very dramatic. Some places, like the San Rafael Knob, within a few miles the elevation changes 2,000 feet.

“The initial work on the access road is part of the history of I-70 and our area. The other three gentlemen who worked on the access road with me have passed away now. I am the only one left who remembers and lived the origins of I-70 first hand. Working on I-70 was a very enlightening experience for me.

“UDOT did a very good job with I-70, there aren’t billboards along the Swell and its natural beauty was maintained throughout the project. This interstate project has enabled more people to see this scenic area. It’s provided access that wasn’t there previously. Some people especially those from back east don’t understand how you can travel for 100 miles across I-70 and never see anyone. It’s a remote area. The road was built with safety in mind and trucks are instructed to check their brakes before they start off from Jerry’s Flat toward Spotted Wolf. Leaving Rattlesnake Bench on the east side of Jerry’s Flat to the San Rafael River, the elevation drops almost 2000 feet. It’s interesting how I-70 came about. It’s amazing how planning a project of this magnitude can be completed in such an inaccessable area as the San Rafael Swell. Few people know that 50 years ago in November 1959, four UDOT men would build an 8 to 10 foot access road into a a four lane highway.” said Spensko.

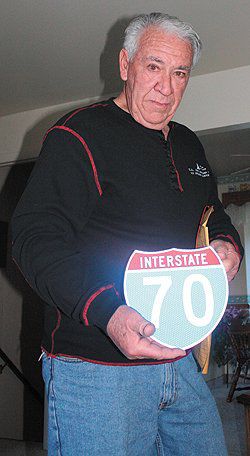

Interstate 70

"Albert Spensko holds the miniature I-70 sign he had made to remember his time on the preliminary work for I-70."